Continuing from Mary Leiter’s story…

As the 19th century ended, the great aristocratic families of Britain began to struggle. A number disappeared, ruined by their expensive lifesetyles, and the depression in agriculture – an estate’s lifeblood – while others clung on for dear life.

For a few hundred families, a miracle came in the form of an American heiress, also known as ‘Dollar Princesses’. By 1895, when nine Dollar Princesses became Ladies, Countesses, Marchionesses and Duchesses, the system had developed into mothers and daughters visiting London for the duration of the social season (April to August).

By the 1930s, some 350 US heiresses had married into the British aristocracy; it’s estimated that they brought (in today’s money) £1 billion with them. Here are some of their stories.

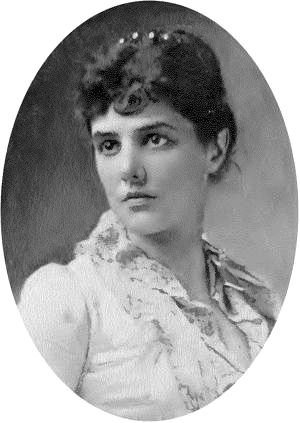

Jennie Jerome in 1880, shortly after her marriage to Sir Randolph Churchill. Robert Huffstutter

Jeanette ‘Jennie’ Jerome was born in Brooklyn in 1854 to Clara and Leonard Jerome. Her father’s fortune was made in stocks, and he was nicknamed ‘the King of Wall Street’.

Jennie was a renowned beauty, and her family was wealthy, making her an ideal bride. However, the New York elite, the so-called Knickerbockers who lived in Manhattan, shunned the Jeromes and their ‘new’ money. Leonard Jerome may have been worth $10 million, the family home on Madison Avenue may have had a 600-seat opera house, and a fountain flowing with real champagne at parties, but they were not accepted by the ‘old’ money of New York; the Knickerbockers were the Astors and the Roosevelts (yes, those Roosevelts) – a real life ‘Great Gatsby’ scenario.

Jennie’s mother took her daughters, Jeanette, Clarita, and Leonie, also known as ‘the Good, the Witty and the Beautiful’, to London and Paris for parties, to help them learn the European way, and mingle with the society elite. Something of a trend for the time, they knew it was a way to marry into the British aristocracy, or at least make new and important connections.

The Jermone mansion in New York. American Buildings Survey – Library of Congess HABS Collection.

Jennie’s mother took her daughters to live in Paris in 1867, following a scandalous escapade involving their father and his numerous mistresses, whom he paraded in his house. The Jerome girls’ education and introduction to society, therefore, followed the manner of the European upper classes.

Known as a dark beauty and called ‘the panther’, the young Jennie had a snake tattooed on her wrist.

Following the invasion of France by Germany in 1870, the Jerome quartet moved to London. Whilst in the English capital, Jennie met The Prince of Wales, future Edward VII; she became a Royal mistress for a short time before he introduced her to Lord Randolph Churchill, son of the powerful Duke of Marlborough. The meeting took place in the summer of 1873 at a sailing regatta on the Isle of Wight, and it was love at first sight. Just three days later, Jennie and Randolph were engaged, in a whirlwind romance.

The couple married in April 1874, almost a year after their engagement, as their parents battled out the particulars of a marriage agreement. The Spencer-Churchills opposed the marriage, but a dowry of $250,000 (around £4.3 million today) from Mr Jerome soon won them over, Blenheim Palace being in a state of disrepair. However, their amorous children couldn’t keep their hands off one another: it is thought 20-year-old Jennie was pregnant by the time she walked down the aisle at the Parisian British Embassy.

Jennie Jerome was the mother of Winston Churchill. Henry Van der Weyde/Wikimedia Commons

Lady Randolph Churchill, as Jennie became, spent much time at Blenheim in the beginning of her marriage; she was stuck with her mother-in-law, The Duchess of Marlborough, as her husband continued his parliamentary career.

It was here she gave birth to her first son, Winston Leonard Spencer-Churchill, future Prime Minister. Not much of a maternal figure, Jennie handed the baby to nanny and left her to it – little would change with regards to her children.

She often travelled around the country, but missed the hustle and bustle of London, and began to find married life difficult. Randolph could be unpredictable and unstable, and Jeanette’s company consisted of her mother-in-law, Frances.

Whilst in Ireland as Randolph served his father, Viceroy of Ireland, Jennie gave birth to the couple’s second son, John, in 1880.

Eventually, Jennie moved to London, to the couple’s house near Marble Arch. Interestingly, their house was the first in London to have electricity.

Aged just eight, Jennie sent her eldest, Winston, to boarding school, and continued with her life of charity work, shopping and entertaining. It appears she did help her husband, by writing some of his speeches, and she is attributed for some of his success and popularity. Lady Randolph had something of a career (as far as a woman could in the late 19th century) of her own, promoting Conservative policies.

With little maternal instinct, Jeanette ignored her son’s pleas to visit him at school, or to allow him home. Once, Winston came home from boarding school for his birthday to find his parents had left for Russia.

By 1887, Randolph had resigned from all his parliamentary positions, out of the blue. This meant no income for Jennie and her family, and divorce was seriously discussed. Lady Randolph kept her husband’s liveries however, determined that Winston would one day make use of them.

Although the marriage survived, the couple were no longer in love but still caring about one another; Jennie and Randolph decided to embark on a world tour.

The London home of Randolph and Jennie in the 1880s. Simon Harriyott

Jennie Churchill had a voracious sex drive, and though she cared for Randolph, she took over 200 lovers, including The Prince of Wales. She was often nicknamed ‘Lady Randy’, and her descendants believe that Randolph was not John’s father, but Evelyn Boscawen, an army officer. Whilst in Europe, Jennie took French lovers, and even had Bismarck’s son falling at her feet.

The couple took a lead-lined coffin with them in case Randolph died whilst abroad, having syphilis; rumours suggest this was down to Jennie’s loose character, though others posit that Randolph had visited prostitutes. Upon their return, aged 44, Lord Randolph Churchill died, his wife nursing him to the end, which came in January 1895.

A widow aged 41, Jennie had to live on a very restricted income. The mighty Spencer-Churchills could now not afford to send Winston to Cambridge. Jennie moved to Paris, where her sisters lived, and she soon fell in love with fellow American, Bourke Cockran, after flirting with her peers in the aristocracy: John Delacour, Lord Wolverton and Lord Astor were amongst those.

Jeanette’s Parisian lovers had come in useful to teach Winston French, Cockran was now instructed to introduce her 22-year-old son to her home city of New York.

Soon after, Jennie came into her own. She started a literary magazine, and even took a hospital ship to South Africa to help in the Boer War effort. She turned her hand to writing and penned a play. Though she was never maternal, Jennie was always ambitious: most importantly, she helped establish Winston, who had inherited her resourcefulness, in politics.

In 1897, at The Duchess of Devonshire’s fancy dress ball, Jennie met George Frederick Middleton Cornwallis, a 23-year-old contemporary of her son’s and fell in love. A handsome man, Jennie married him against protests from family and friends (including Edward, Prince of Wales) in 1900, with her eldest son at her side.

When Edward VII was crowned in 1902, Lady Randolph sat in a special pew in Westminster Abbey, along with other mistresses of the new King. The box was dubbed ‘the loose box’, as Jennie sat alongside the likes of Alice Keppel and Lillie Langtry, but it shows she was still considered a lady of important standing in society.

While title and money had not mattered when she was smitten with Randolph, the widow thought her new beau was to inherit two estates: he was, in fact, broke. George declared himself bankrupt in 1914, and Jennie divorced him, changing her name back to Lady Randolph Churchill.

Jennie was not yet done with marriage, despite being in her early 60s. Montagu Porch, the 32-year-old son of a Somerset landowner, then caught her eye and she married him in 1918 at Harrow register office.

Her death was unexpected: visiting a friend in Somerset, Jennie slipped on the staircase and fractured her leg badly. Gangrene set in and her leg was amputated to save her life; a few months later, in June 1921, a haemorrhage proved fatal.

Winston, who had found a loving wife and no longer sought his mother’s affection, wrote of her death: “I do not feel a sense of tragedy but only loss. Her life was a full one. The wind was in her veins.”

Porch returned from abroad too late to see his wife one last time, and only had her debts to keep him company.

Jennie Jerome, another of the Dollar Princesses, asked to be buried alongside her first husband, who brought her into the British aristocracy and elite society. She is buried in Bladon, Oxfordshire, near her first English home of Blenheim.

Winston Churchill went on to become one of the most famous politicians in British history, leading the country through the Second World War, as his mother instilled a sense of importance and leadership in her son.

1 comment

Thank You Wonderful Life May God Bless Them All